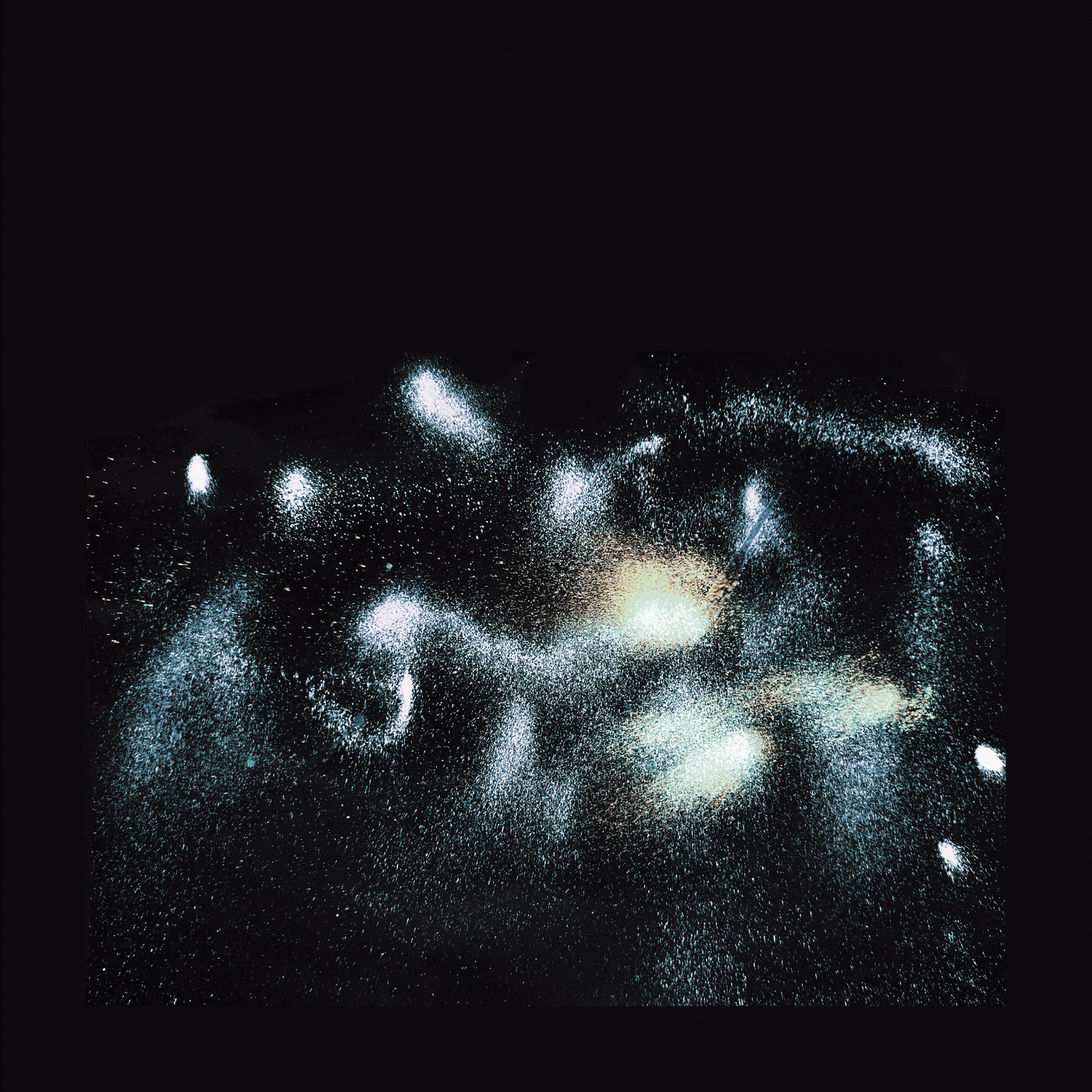

The Hum

—

Out May 12

—

Warp Records

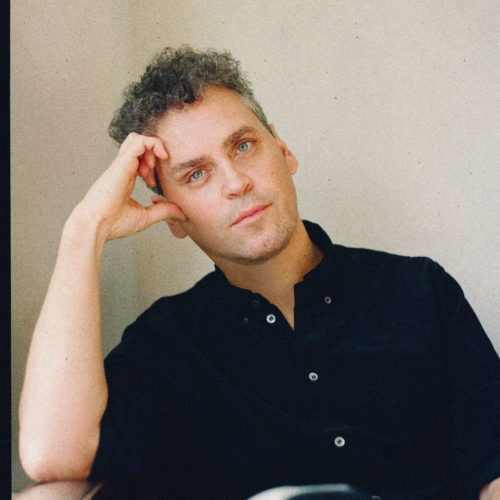

James Ford has been hidden in plain sight for his entire two-decade-long career. The composer, multi-instrumentalist, producer and songwriter has worked with some of the biggest names in music, from Arctic Monkeys to Depeche Mode via Foals, Gorillaz and Kylie Minogue, but has always dedicated himself to the success of these projects almost to the point of self-erasure. Even as one half of Simian Mobile Disco, alongside longtime creative partner Jas Shaw (and as a touring member of The Last Shadow Puppets) his role has often appeared selfless, working more towards a collective goal. But for the first time he is about to move centrestage himself and the results will blindside everyone.

He has deftly side-stepped the obvious choice of flicking through his contacts to produce a press-worthy pop album with a galaxy of A-list feature appearances; he has ignored the commercial temptation of making a “rent-a-rapper” mega-producer’s hip-hop folly; and he has even refused point blank to occupy the tactical safe ground of highly polished EDM or abstract electronica. What he has done is release one of the most bewitching and persuasive albums 2023, as much homage to the tender and eccentric English pop music of Brian Eno and Robert Wyatt as it is love letter to his wife and son’s Palestinian roots; as much exploration of the pastoral verve of Canterbury prog as it is informed by the dynamics of modern hip-hop production; as much a madcap Radiophonic voyage into the cosmic unknown as it is successful experiment into writing classic heartbreaking anthems for the ages. With The Hum, James Ford has finally come out of hiding.

The genesis of the album lay in his decision to build a studio in the family home in 2017 allowing him the luxury of sonic experimentation. But as soon as the construction was complete his life changed dramatically in other ways. He became a dad for the first time (“Domesticity informs the album”). Having a soundproof room full of gear meant he could fire up a modular synth or even play drums without waking his young son sleeping downstairs.

But there was bad news as well. His SMD partner Jas Shaw was diagnosed with a rare disease, AL amyloidosis, which meant that Simian Mobile Disco were now on hiatus. James says: “It put an end to touring and even us going into the studio together (for his safety). The lack of having Simian Mobile Disco as an outlet to make music for myself, probably forced my hand to make a solo record. My life changed dramatically overnight. I went from a lifestyle of almost constant travel to one where I barely left the house.”

Slowly but surely his hard drive began to fill up with the results of sonic experiments and that was when the epiphany struck him: “‘I always collaborate – even in SMD, everything I do is a collaboration – but what would happen if I finished a project on my own?’ It struck me, ‘Oh shit, maybe I’m making a solo record.’ Which is a weird thing to think at the age of 40.”

He confesses that initially the temptation to scroll through his iPhone and call on a lot of people he knew for help was strong: “I was making tracks and thinking, ‘Maybe I’ll send this to Alex Turner (Arctic Monkeys).’ It genuinely did cross my mind that I could make an album with a lot of guest features but it just felt braver for me to do it on my own.”

So suddenly, from out of nowhere almost, he found himself making a solo record on which he did absolutely everything. The kit list includes piano, Wurlitzer, Clavinet, bass clarinet, flute, tenor sax, Serge modular, ARP 2600, Maxikorg, Oberheim, hammered dulcimer, cello, Philicorda organ and vibraphone not to mention bass, drums and guitars. In fact James learned bass clarinet specifically for the album. He cites his years in Manchester pre-Simian, soaking up the can-do attitude of Graham Massey, of acid house legends 808-State, and cosmic outsider artist Paddy Steer, as a huge influence but also he looked to landmark records by eccentric multi-instrumentalist auteurs such as Todd Rundgren, Haruomi Hosono, Nick Lowe and Ivor Cutler.

The confidence inspired by having a home studio to experiment in was such that he played everything live, with no sequencing, no soft synths and no DAW. Music was recorded straight to tape on first or second pass, giving it vital immediacy: “With technology it’s easy to fix ‘mistakes’ after the event, and I really hate this point we’ve arrived at in recording history. So I didn’t put things in time and didn’t even edit on the computer. Because of the approaching AI nightmare, humanness is the main positive quality you can add to a record.”

But playing everything himself was easy compared to having to sing: “I’d never sung in public before. I’d never done karaoke. I don’t even sing in the shower! I’m always telling artists to lean into their vulnerability [in the studio] and suddenly I had to apply some of these ideas to myself. I ended up with a taste of my own medicine!”

He pinpoints lyric writing as the most difficult aspect of the whole endeavour: “A lot of the lyrics concern me adjusting to changes in life: becoming a dad, getting older, my friend getting ill. Having kids is a huge, positive paradigm shift – you’re no longer the centre of the world – but both that and the situation with Jas made me consider my own mortality for the first time. The lyrics deal with this change and have a nostalgia for the times that have gone. But also I’m looking outwards at the world my son will inherit with an increasing sense of unease. I’m fairly preoccupied with the tightrope we’re walking as a species.”

He was delighted when the project got signed to Warp: “Basically Broadcast are one of my all time favourite bands and Aphex Twin is one of my all time favourite artists. In the early Simian days Jas and I totally bonded over Autechre. Even before that I was in this crap band when I was a student and one day Warp phoned and said they were going to come and see us play. I’d literally never been more excited in my life. So the fact that The Hum is coming out on Warp, to me, is an act of coming full circle. They’re my all-time favourite label.”

The opening track on the album ‘Intro’, along with ‘The Hum’, is one of two lush, layered tape experiments which act as archaeological clues as to how the project sounded originally, with all of the music initially being a collection of highly textural ambient pieces influenced by Harold Budd and the groundbreaking Brian Eno and Robert Fripp collaboration, No Pussyfooting. The vaporous, celestial shimmer was created by having two tape machines feeding back into one another, utilising a huge tape loop which snaked around mic stands dotted about his studio.

The lazy, blissful, hypnopompic vibe of ‘Pillow Village’ sets the tone for the album, achieving a stately sweet spot which is full of love but also melancholy; a joyful downer set to tape, with slowly evolving chord patterns harking back to the somnambulist tracks on Miles Davis’ Live-Evil but also the kind of prog his dad played when he was young such as Gentle Giant, Soft Machine and Caravan. ‘I Never Wanted Anything’ concerns the middle-years realisation that most of life’s opportunities are starting to retreat from view, but being comfortable with it. As James says: “I feel incredibly lucky that I’ve managed to keep doing what I do. When I play music and I get the feeling that it’s going to be amazing? That’s literally the buzz that I chase every day.” The spirit of Brian Eno’s Another Green World hovers in the background: “It’s a Desert Island Disc; a failsafe. We were lucky enough to work with Eno on the second Simian LP just as I was thinking of moving properly into production, so it was an experience to see how his attitude changed things. His intelligence in these matters is second to none. What he does [on early solo records] is quite playful, almost borderline silly in places, but it has a depth of artistic temperament which I love and have been most drawn to throughout my whole life.”

‘The Yips’ is centred round a massive Can-like groove (“Yeah, Jaki Liebezeit is an all-time hero”) but, geographically and musically speaking, the main influence isn’t German but Middle Eastern: “My wife is half-Palestinian and my son has Palestinian roots, so a few years ago I visited the territories feeling the need to connect with the culture and people there. It was both inspirational and incredibly depressing. I met lots of inspiring musicians young and old that were just trying to live and create music in very difficult circumstances.”

Lyrically ‘Golden Hour’ concerns satori, a Buddhist term meaning complete understanding, a heightened state of awareness that might come during meditation or a psychedelic experience: “Everything is laid out in perfect harmony. You figure it all out but as you’re coming back to reality you try and grab onto the sense of it but you’re like, ‘Hold on, this doesn’t make any sense any more.’ You just had the meaning of life in your hands but then it slips through your fingers.” With the outrageous funk rock monster ‘Caterpillar’ James wanted to slough off the feeling of him being just one guy in a studio singing songs to himself and imagined into being a behemoth groove as if “made by a bunch of crazy guys in a room, like Parliament/Funkadelic or [prog supergroup] Rhinoceros”.

He arguably saves his most bravura moment for last though. ‘Closing Time’ is a timelessly melancholy ballad that could easily sit on a classic album by Robert Wyatt or Paul McCartney. It’s ostensibly about last orders being called in a pub, but with a strong undertow relating to the transience of life and the future of humanity itself: “I love sappy songs but it was so far out of my comfort zone to actually write one. It was a case of, ‘Just fucking get over yourself and have a go!’ It’s definitely about getting older and coming to terms with mortality. It’s not really talked about in western society but it’s healthy to find a way to be comfortable with death, to try and get rid of the fear of it. The world is changing quickly and part of the problem is that people can’t deal with this. They can’t let things go and move on.”

When asked if he feels like this album is giving him a chance to say something fundamental about himself for the first time, James Ford nods vigorously: “Yeah, I think so, and maybe that’s why I feel so nervous about it. It’s as close to my heart as it can be without me spelling everything out.” But his nerves should be assuaged, with The Hum he has finally stepped into the spotlight.